Father Mapple delivers his sermon on the story of Jonah – the Biblical tale that Moby-Dick evokes more than any other. Not just in the prominent presence of the whale, but in the themes of a man defying his fate, and struggling to avoid his fated destiny. If you haven’t read the story of Jonah, you should, especially if you want to understand Moby-Dick.

I’m far from a church-going man, but I regularly attended Mass all the way through my high school graduation. I don’t recall the Book of Jonah coming up even once, though I’m sure it did at some point. It’s an easy story to remember: a man defies God, is swallowed whole by a whale, then released when he prays for forgiveness and deliverance. But it’s very much an Old Testament story, with an angry and vengeful God, with little relevance to the kind of happy loving messaging that modern Christianity focuses on.

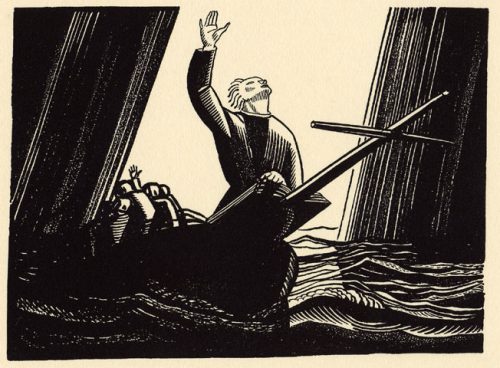

The sermon that Father Mapple delivers is much more in the spirit of old time 19th Century Christianity, a sermon that doesn’t hold back the fire and brimstone. There’s a fabulous description of Jonah as he seeks a ship to take him across the sea:

Miserable man! Oh! most contemptible and worthy of all scorn; with slouched hat and guilty eye, skulking away from his God; prowling among the shipping folk like a vile burglar hastening to cross the seas. So disordered, self-condemning is his look, that had there been policemen in those days, Jonah, on the mere suspicion of something wrong, had been arrested ere he touched a deck. How plainly he’s a fugitive! no baggage, not a hat box, valise or carpet-bag,-no friends accompany him to the wharf with their adieux.

We shall later see, when Ishmael and Queequeg sail with from Nantucket aboard the Pequod, that they too will have no friends but each other to accompany them to the wharf and say their goodbyes.

What lessons does Father Mapple take from the story of Jonah? The first, that a man who has been punished should first be repentant, and accept the punishment as just:

He goes down in the whirling heart of such a masterless commotion that he scarce heeds the moment when he drops seething into the yawning jaws awaiting him; and the whale shoots-to all his ivory teeth, like so many white bolts, upon his prison. … sinful as he is, Jonah does not weep and wail for direct deliverance. He feels that his dreadful punishment is just. He leaves all his deliverance to God, contenting himself with this, that spite of all his pains and pangs, he will still look toward His holy temple.

This attitude of acceptance is, of course, the complete opposite of that taken by Captain Ahab, who has yet to enter the story. Rather than accepting the loss of his leg, Ahab is consumed by vengeance and rage, ultimately leading himself, his ship and his crew to their deaths.

Yet there is another lesson Father Mapple draws from the story:

Woe to him whom this world charms from Gospel duty! Woe to him who seeks to pour oil upon the waters when God has brewed them into a gale! Woe to him who seeks to please rather than appall! Woe to him whose good name is worth more to him than goodness! Woe to him who, in this world, courts not dishonor!

This could be Ahab’s crew, who recklessly followed their master even as they came to realize he was leading them on a mad quest for vengeance. It could apply to Ahab himself, who allows his own desire for vengeance to direct him rather than the directives laid down by the ship’s owners. It could even be Ishmael, who rather than pursuing a sedate life on land chose to flee to sea.

Yet there is one important and telling way where Jonah’s story parts from that of Moby-Dick. In the end of all his hardships, God is merciful, and Jonah is released from the whale. In Moby-Dick, everyone is punished for the Ahab’s sin, and all drowned, the good and the evil alike. God, or perhaps a more impartial Fate or Destiny, has no mercy in Melville’s world.

For a great rendition of this scene, take a look at Orson Welles as Father Mapple in the movie version of Moby-Dick:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mog0W6Jwj0Q