Moby-Dick has a great talent for introducing small characters with great presence. Their are examples of this throughout the book: Elijah, the mentally unbalanced sailor and prophet; the cook, who serves as Stubb’s conscious; the innkeeper who greets Ishmael at his arrival in New Bedford. The most momentous of these may be Father Mapple, the preacher who delivers one of the most important passages of the novel.

The Pulpit serves as his introduction. When we left Ishmael, he and the rest of the congregation waited in the chapel for the arrival of the preacher. Father Mapple’s reputation proceeds him – while he had been a sailor and a harpooneer in his youth, he had dedicated the rest of his life to God and the ministry. Yet he still bears the signs of his previous profession:

Father Mapple was in the hardy winter of a healthy old age; that sort of old age which seems merged into a second flowering of youth, for among all the fissures of his wrinkles, there shown certain mild gleams of a newly developed bloom-the spring verdure peeping forth beneath February’s snow. No one having previously heard his history, could for the first time behold Father Mapple without the utmost interest, because there were certain engrafted clerical peculiarities about him, imputable to that adventurous maritime life he led. When he entered I observed that he carried no umbrella, and certainly had not come in his carriage, for his tarpaulin hat ran down with melting sleet, and his great pilot cloth jacket seemed almost to drag him to the floor with the weight of the water it had absorbed.

Like a sailor, who must perform his duty no matter the weather, Father Mapple does not flinch from enduring the elements in pursuit of his duty. Still more in keeping with his past job is the pulpit from which he preaches, and which he now ascends:

Like most old fashioned pulpits it was a very lofty one, and since a regular stairs to such a height would, by its long angle with the floor, seriously contract the already small area of the chapel, the architect, it seemed, had acted upon the hint of Father Mapple, and finished the pulpit without stairs, substituting a perpendicular side ladder, like those used in mounting a ship from a boat at sea … Halting for an instant at the foot of the ladder, and with both hands grasping the ornamental knobs of the manropes, Father Mapple cast a look upwards, and then with a truly sailor-like but still reverential dexterity, hand over hand, mounted the steps as if ascending the main-top of his vessel … I was not prepared to see Father Mapple after gaining the height, slowly turn round, and stooping over the pulpit, deliberately drag up the ladder step by step, till the whole was deposited within, leaving him impregnable in his little Quebec.

As a side-note, Quebec at the time was a notorious fortress city, also known as the “Gibraltar of North America.”

Father Mapple evokes not only his seafaring past, but also the peculiar loneliness of the sailor by isolating himself at his pulpit. He draws up the ladder behind him, isolating himself from the surrounding world, “for replenished with the meat and wine of the Word, to the faithful man of God, this pulpit, I see, is a self-containing Ehrenbreitstein, with a perennial well of water within the walls.”

What a contrast with Ishmael, a man plagued with doubts and questions! Father Mapple isolates himself with only his faith and the word of God to sustain him, and does so of his own volition. Ishmael, on the other hand, is uncertain of his own future. He has no ties to a profession or a home, and finds himself seeking the sea not because that is his calling, but as a way to salve his own uncertainties and depression.

But there is still more to the pulpit that has not yet been described:

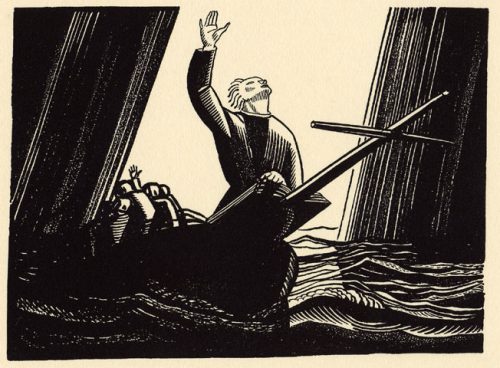

Between the marble cenotaphs on either hand of the pulpit, the wall which formed its back was adorned with a large painting representing a gallant ship beating against a terrible storm off a lee coast of black rocks and snowy breakers. But high above the flying scud and dark-rolling clouds, there floated a little isle of sunlight, from which beamed forth an angel’s face; and this tiny bright face shed a distinctive spot of radiance upon the ship’s tossed deck … “Ah, noble ship,” the angel seemed to say, “beat on, beat on thou noble ship, and bear a hardy helm; for lo! the sun is breaking through; the clouds are rolling off-serenest azure is at hand.”

The message here is clear enough – God provides hope even in the face of greatest adversity. But is God’s help truly there if one’s fate is shipwreck and death? Faith certainly lends little help to the Pequod and its crew at the book’s conclusion.

But there is one final ship-like touch to the pulpit’s design: “Its panelled front was in the likeness of a ship’s bluff bows, and the Holy Bible rested on a piece of scroll work, fashioned after a ship’s fiddle-headed beak.”

Ishmael draws a metaphor of the pulpit as a ship drawing all the world behind it, as the prow draws a boat. “Yes the world’s a ship on its passage out, and not a voyage complete; and the pulpit is its prow.” This is in keeping with Moby-Dick’s focus on fate and destiny – the fate of the world is beyond the control of individuals, and instead in the hands of God. In the view of the Father Mapple’s of the world, this is a good thing.

But consider this passage from the final chapter of Moby-Dick:

Hearing the tremendous rush of the sea-crashing boat, the whale wheeled round to present his blank forehead at bay; but in that evolution, catching sight of the nearing black hull of the ship; seemingly seeing in it the source of all his persecutions; bethinking it-it may be-a larger and nobler foe; of a sudden, he bore down upon its advancing prow, smiting his jaws amid fiery showers of foam.

The prow leads the ship, but not to safety in God’s hands, but to destruction at the jaws of the Whale, which as we shall see in the next chapter can itself be God’s instrument.