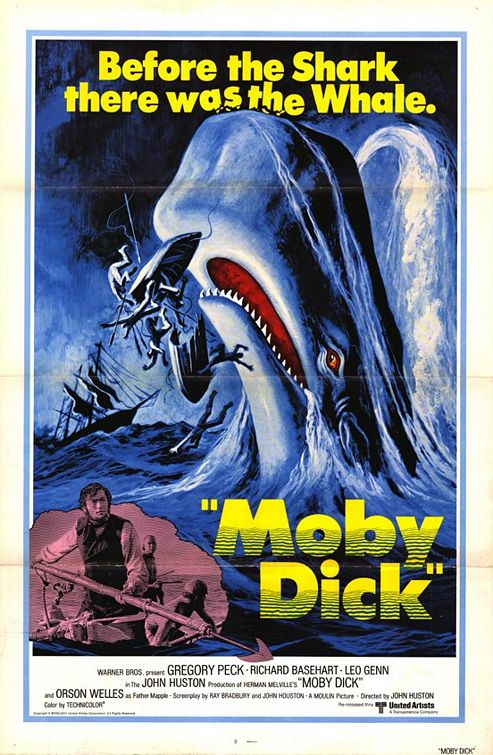

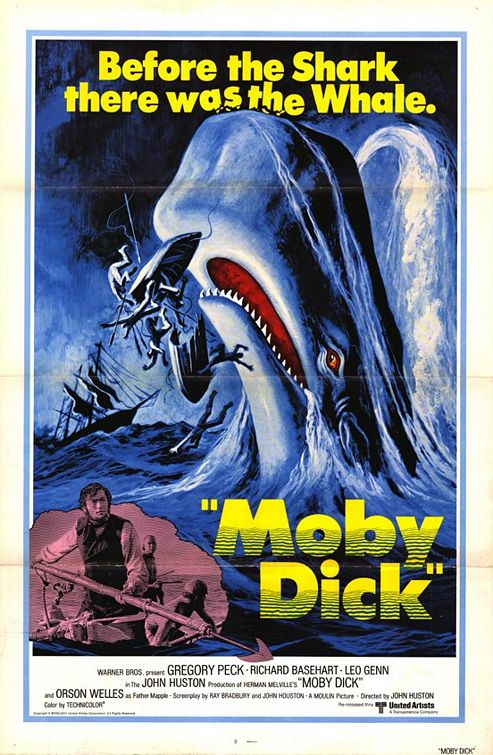

Poster for a 1976 theatrical re-release of the 1956 movie version of Moby Dick

When I was a small child, I saw the 1956 movie version of Moby Dick. I didn’t understand it. The dialogue was incomprehensible, and the visual effects nothing special compared to Star Wars or Back to the Future. But something about the film stuck with me. Perhaps it was Gregory Peck’s depiction of Captain Ahab, with his low growling voice and somber Quaker hat. Or the brilliantly shot ocean setting, filled with soaring seabirds, sails snapping taut in the wind, and singsong shanties. Or perhaps it was the whales themselves, more implied then seen given the special effects of the time, but their bulk and strength still apparent as they awed and frightened the sailors.

I watched the film repeatedly, eventually driving my parents to purchase a VHS copy rather than constantly renting the same film from our local video store. I played at being a whaler, rowing the couch across the living room carpet and harpooning the coffee table with a golf club. While other boys played with trucks or trains, I had a plastic sperm whale that I swung about until its paint and fins wore off. To me, Moby-Dick was the greatest action and adventure film I’d ever seen, flawed only by the occasional extended scene of talking. After a year or so my obsession faded, and I moved on to dinosaurs, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and other more traditional childhood passions.

A few years later I found a leather bound copy of Moby-Dick on my parent’s bookshelf. I was not an early reader, but once I had learned I had become a voracious one. I’d successfully tackled Harry Potter, Animorphs, and Tom Sawyer. Surely Moby-Dick wouldn’t be too much more trouble. I was wrong. By the time I hit the second page I had no idea what Melville was talking about, and I gave up.

But I didn’t abandon the project, returning every few years to hunt for the adventurous sea tale I knew was waiting somewhere within. I skipped anything dealing with free will and destiny, and ignored treatises on morality and God. Instead I zoomed in on the adventure story that rattled about inside the book’s philosophical framework. I found the story of the friendship between Ishmael and Queequeg, a friendship defying barriers of race, class and culture. I found the Pequod, a “cannibal of a craft, tricking herself out in the chased bones of her enemies”. I found the story of a Captain Ahab driven mad by the loss of his leg, who’d “strike the sun if it insulted me,” and pursued the object of his vengeance around the tip of South America and into the Sea of Japan. Through raging storms, lit by the flickering light of St. Elmo’s Fire along the rigging, and against the wishes of his first officer Starbuck, Ahab rolled on, until his rage and madness at last dragged the ship and all its crew but one into the depths of the sea.

I finished the book in high school after several attempts. I could finally say that I had read the thing, and I had no intention of reading it again. Completing it had been a struggle, and most of it had gone over my head, which bothered me. I knew there was more to it than the simple story of Ahab, but I lacked the knowledge required to get the many references to the Bible or classical mythology, or the patience to dig deeper into each passage. In wasn’t until college that I realized that Melville’s book had touched on virtually every subject I studied, from biology to psychology to philosophy and history. The book was like a little world, encapsulating not just a high seas adventure, but also the entire 19th century whaling industry, as well as an examination of the nature of good and evil, an introduction to whale biology as it was understood at the time, and much more. I found myself returning to the book, knowing the story, but looking for what lay behind it. Since then I’ve re-read the novel several times, and can’t say I’ve come any closer to understanding everything that Melville’s masterpiece contains. As each layer of meaning comes clear, it only reveals more ideas and questions to be explored.

By blogging this latest read through, I hope to approach the story from a new angle. I will post once a week on a single chapter, starting from Chapter 1. I’m not quite sure what the nature of many of these posts will be – I’m leaving myself room to write about literary criticism, historical analysis, my own opinions of the characters, or whatever else should strike my fancy. Moby-Dick is a broad book, and it would not do to limit oneself when writing about it.

I also hope that this blog might will inspire readers to pick up Moby-Dick for the first time, or to return to it if they, like many, have given it a try and given up. Moby-Dick is a difficult book, but it rewards perseverance. And I hope this blog can help a little along the way.